Your First GenJAX Model

From Sets to Simulation

Remember Chibany’s daily meals? We listed out the outcome space $\Omega = \{HH, HT, TH, TT\}$ and counted possibilities.

Now we’ll teach a computer to generate those outcomes instead!

The Generative Process

Each day:

- Lunch arrives — randomly H or T (equal probability)

- Dinner arrives — randomly H or T (equal probability)

- Record the day — the pair of meals

In GenJAX, we express this as a generative function.

Your First Generative Function

Here’s Chibany’s meals in GenJAX:

| |

Important: Use flip(), not bernoulli()

GenJAX has two functions for Bernoulli distributions: flip(p) and bernoulli(p). Always use flip(p) - it works correctly as your intuition expects!

The bernoulli(p) function expects the parameter to be the logit value of the coinflip, which is less intuitive for our purposes. The flip(p) function works as expected and is what the official GenJAX examples use.

Example of the bug:

bernoulli(0.9)produces ~71% instead of 90% ❌flip(0.9)produces ~90% as expected ✅

This tutorial uses flip() throughout to ensure correct behavior.

📐→💻 Math-to-Code Translation

How mathematical concepts translate to GenJAX:

| Math Concept | Mathematical Notation | GenJAX Code |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome Space | $\Omega = \{HH, HT, TH, TT\}$ | @gen def chibany_day(): ... |

| Random Variable | $X \sim \text{Bernoulli}(0.5)$ | flip(0.5) @ "lunch" |

| Probability | $P(A) = \frac{|A|}{|\Omega|}$ | jnp.mean(condition_satisfied) |

| Event | $A = \{HT, TH, TT\}$ | has_tonkatsu = (days[:, 0] == 1) | (days[:, 1] == 1) |

Key insights:

- @gen function = Generative process defining Ω

- flip(p) = Random variable with probability p (Bernoulli distribution)

- @ “name” = Label the random choice (for inference later)

- Simulation + counting = Computing probabilities

Breaking It Down

Line 1: @gen

- Tells GenJAX: “This is a generative function”

- GenJAX will track all random choices

Line 2-3: Function definition

def chibany_day():defines the function- The docstring explains what it does

Line 6: First random choice

| |

flip(0.5)— Flip a fair coin (50% chance of 1, 50% chance of 0)@ "lunch"— Name this random choice “lunch”- Store the result in

lunch_is_tonkatsu

Line 9: Second random choice

| |

- Another coin flip, named “dinner”

Line 12: Return value

| |

- Returns a tuple (pair) of the two values

- This is like one outcome from $\Omega$!

Running the Function

Generating One Day

| |

Output (example):

Today's meals: (0, 1)What You’ll Actually See

When you run this code, you’ll see output like:

Today's meals: (Array(0, dtype=int32), Array(1, dtype=int32))Don’t panic! This is because GenJAX returns JAX arrays, not plain Python numbers.

Why the difference? (Click to expand)

What you see: Array(0, dtype=int32) or Array(1, dtype=int32)

What it means:

Array(0, dtype=int32)= 0 = HamburgerArray(1, dtype=int32)= 1 = Tonkatsu

Why JAX does this: JAX uses arrays for everything to enable fast computation on GPUs. These are JAX’s way of representing numbers that can run efficiently on both CPUs and GPUs.

To get simple numbers, you can convert:

| |

For this tutorial: Just remember that Array(0, dtype=int32) is just a fancy way of saying 0, and Array(1, dtype=int32) means 1.

This means: Hamburger for lunch (0), Tonkatsu for dinner (1) — or in our notation: $HT$!

What’s a ‘key’?

JAX uses random keys to control randomness. Think of it like a seed — the same key always gives the same “random” results, which helps with reproducibility.

Don’t worry about the details! Just know:

- Create a key with

jax.random.key(some_number) - Split it for multiple uses with

jax.random.split(key, n)

Accessing the Random Choices

| |

Output (for the trace above):

Lunch was tonkatsu: 0

Dinner was tonkatsu: 1Expected Output

You’ll actually see:

Lunch was tonkatsu: 0

Dinner was tonkatsu: 1Good news: When accessing individual choices with choices['lunch'], GenJAX gives you plain numbers (0 or 1), not the wrapped Array(...) format! This makes them easier to work with.

Simulating Many Days

Now let’s generate 10,000 days!

| |

What’s vmap?

vmap stands for “vectorized map” — it runs a function many times in parallel, which is very fast!

Think of it like: “Do this 10,000 times, but do them all at once instead of one-by-one”

Counting Outcomes

Now we have 10,000 days. Let’s count how many have at least one tonkatsu:

| |

Output (example):

Days with tonkatsu: 7489 out of 10000

P(at least one tonkatsu) ≈ 0.749Remember from the probability tutorial: The exact answer is $3/4 = 0.75$!

With 10,000 simulations, we got very close: $0.749 \approx 0.75$

📘 Foundation Concept: Simulation vs. Counting

Recall from Tutorial 1, Chapter 3 that probability is counting:

$$P(A) = \frac{|A|}{|\Omega|} = \frac{\text{outcomes in event}}{\text{total outcomes}}$$

We calculated $P(\text{at least one tonkatsu}) = \frac{|{HT, TH, TT}|}{|{HH, HT, TH, TT}|} = \frac{3}{4} = 0.75$ by hand.

Now with GenJAX, we simulate instead of enumerate:

| Tutorial 1 (By Hand) | Tutorial 2 (GenJAX) |

|---|---|

| List all outcomes: {HH, HT, TH, TT} | Generate 10,000 samples |

| Count favorable: 3 out of 4 | Count favorable: ~7,500 out of 10,000 |

| Divide: 3/4 = 0.75 | Divide: 7,500/10,000 ≈ 0.75 |

Why simulate?

- Tutorial 1 approach breaks down with complex models (too many outcomes to list)

- Simulation scales: same code works whether Ω has 4 outcomes or 4 billion

- As simulations increase (10K → 100K → 1M), we get closer to exact answer

The principle is identical — count favorable outcomes and divide by total. But simulation lets us handle models that are impossible to enumerate by hand!

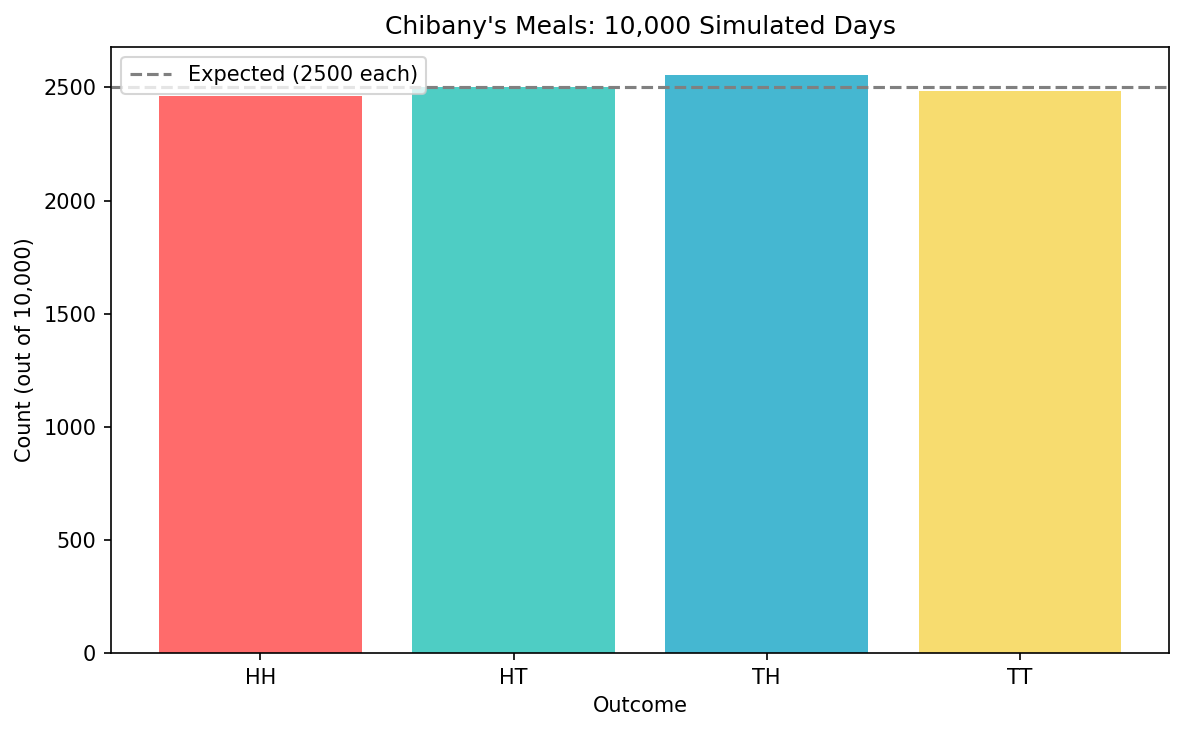

Visualizing the Results

Let’s make a bar chart showing all four outcomes:

| |

What you’ll see: Four bars of roughly equal height (around 2500 each), matching our theoretical expectation of $1/4$ for each outcome!

Interactive Exploration

📓 Interactive Notebook

Try the interactive notebook - Open in Colab with live sliders and visualizations! It includes all the code from this chapter plus interactive widgets to explore how changing parameters affects the results.

The companion notebook has interactive widgets so you can:

Slider 1: Probability of Tonkatsu for Lunch

- Move the slider from 0.0 to 1.0

- See how the distribution changes!

Slider 2: Probability of Tonkatsu for Dinner

- Make dinner independent from lunch

- Or make tonkatsu more/less likely at different meals

Slider 3: Number of Simulations

- Try 100, 1,000, 10,000, or even 100,000 simulations

- See how the estimate gets more accurate with more simulations

The chart updates automatically as you move the sliders!

Try This!

In the Colab notebook:

- Set lunch probability to 0.8 (80% tonkatsu)

- Set dinner probability to 0.2 (20% tonkatsu)

- Run 10,000 simulations

- What do you notice about the distribution?

Answer: Outcomes with tonkatsu for lunch (TH, TT) are much more common than those without (HH, HT)!

Connection to Set-Based Probability

Let’s connect this back to what you learned:

| Set-Based Concept | GenJAX Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Outcome space $\Omega$ | Running simulate() many times |

| One outcome $\omega$ | One call to simulate() |

| Event $A \subseteq \Omega$ | Filtering simulations |

| $|A|$ (count elements) | jnp.sum(condition) |

| $P(A) = |A|/|\Omega|$ | jnp.mean(condition) |

Example:

Set-based:

- Event: “At least one tonkatsu” = $\{HT, TH, TT\}$

- Probability: $|\{HT, TH, TT\}| / |\{HH, HT, TH, TT\}| = 3/4$

GenJAX:

| |

It’s the same concept! Just computed instead of counted by hand.

Understanding Traces

When you run chibany_day.simulate(key, ()), GenJAX creates a trace that records:

- Arguments — What inputs were provided (none in this case)

- Random choices — All the random decisions made, with their names

- Return value — The final result

| |

Output (example):

Return value: (Array(False, dtype=bool), Array(False, dtype=bool))

Choices: {'lunch': Array(False, dtype=bool), 'dinner': Array(False, dtype=bool)}

Log probability: -1.3862943611198906What this means:

- Return value: The pair of meals (both False = both Hamburger = HH)

- Choices: A dictionary of all named random choices and their values

- Log probability: The log-likelihood of this particular outcome ($\log(0.5 \times 0.5) = \log(0.25) \approx -1.386$)

Why Track Everything?

Tracking all random choices is essential for inference — when we want to ask “given I observed this, what’s probable?”

We’ll see this in action in Chapter 4!

Exercises

Try these in the Colab notebook:

Exercise 1: Different Probabilities

Modify the code so:

- Lunch is 70% likely to be tonkatsu

- Dinner is 30% likely to be tonkatsu

Hint: Change the flip(0.5) values!

Exercise 2: Counting Tonkatsu

Write code to count how many tonkatsu Chibany gets across all simulated days (not just which days have tonkatsu, but the total count).

Hint: Add up days[:, 0] + days[:, 1]

Exercise 3: Three Meals?

Extend the model to include breakfast! Now Chibany gets three meals per day.

What You’ve Learned

In this chapter, you:

✅ Wrote your first generative function

✅ Simulated thousands of random outcomes

✅ Calculated probabilities through counting

✅ Visualized distributions

✅ Understood the connection between sets and simulation

✅ Learned about traces and random choices

The key insight: Generative functions let computers do what you did by hand with sets — but now you can handle millions of possibilities!

Next Steps

Now that you can generate outcomes, the next question is:

What if I observe something? How do I update my beliefs?

That’s inference, and it’s where GenJAX really shines!

| ← Previous: Python Essentials | Next: Understanding Traces → |

|---|