The Continuum: Continuous Probability

From Counting to Measuring

Chibany stares at their histogram. They understand expected value now. The 455g average makes sense as a mixture of 500g tonkatsu and 350g hamburger bentos.

But something still bothers them.

Look at these actual measurements from their first week:

Monday: 520g (tonkatsu)

Tuesday: 348g (hamburger)

Wednesday: 505g (tonkatsu)

Thursday: 362g (hamburger)

Friday: 488g (tonkatsu)The weights aren’t exactly 500g and 350g! They vary.

And here’s the deeper question: What’s the probability that a bento weighs exactly 505.000000… grams?

Chibany realizes: in Tutorial 1, they learned probability by counting discrete outcomes. But weight isn’t discrete. It’s continuous. There are infinitely many possible values between 340g and 520g.

How do you assign probabilities when there are infinitely many possibilities?

The Problem with Discrete Probability

Let’s see why the discrete approach breaks down.

In Tutorial 1, Chibany used this formula: $$P(\text{event}) = \frac{\text{# of outcomes in event}}{\text{# of total outcomes}}$$

This worked because there were finitely many outcomes:

- Outcome space: {tonkatsu, hamburger}

- $P(\text{tonkatsu}) = \frac{1}{2}$ if choosing randomly

But with continuous weight, this breaks:

- Outcome space: all real numbers between (say) 340g and 520g

- $P(\text{weight} = 505g \text{ exactly}) = \frac{1}{\infty} = 0$

Every specific weight has probability ZERO!

This seems wrong. Chibany definitely observed 505g. How can something that happened have zero probability?

📘 Foundation Concept: From Counting to Measuring

Remember from Tutorial 1 that probability started with counting:

$$P(A) = \frac{|A|}{|\Omega|} = \frac{\text{outcomes in event}}{\text{total outcomes}}$$

This worked perfectly for discrete outcomes like {hamburger, tonkatsu} because:

- We could count the outcomes (|Ω| = 2)

- Each outcome got equal “share” of probability (1/2 each)

- The formula made intuitive sense

But with continuous variables like weight, we can’t count outcomes:

- Infinitely many possible values between 340g and 520g

- Can’t divide by infinity (|Ω| = ∞)

- The counting formula breaks down

The key transition: Instead of counting discrete outcomes, we’ll measure continuous areas. The logic stays the same (favorable / total), but:

- Discrete: Count outcomes → divide by total count

- Continuous: Measure area → divide by total area

Chibany’s realization: “I need a new tool for this new type of problem, but the core idea of probability hasn’t changed!”

The Resolution: Probability Density

The solution is to stop asking about exact values and start asking about ranges.

Instead of:

- ❌ “What’s P(weight = 505g)?” (answer: 0)

Ask:

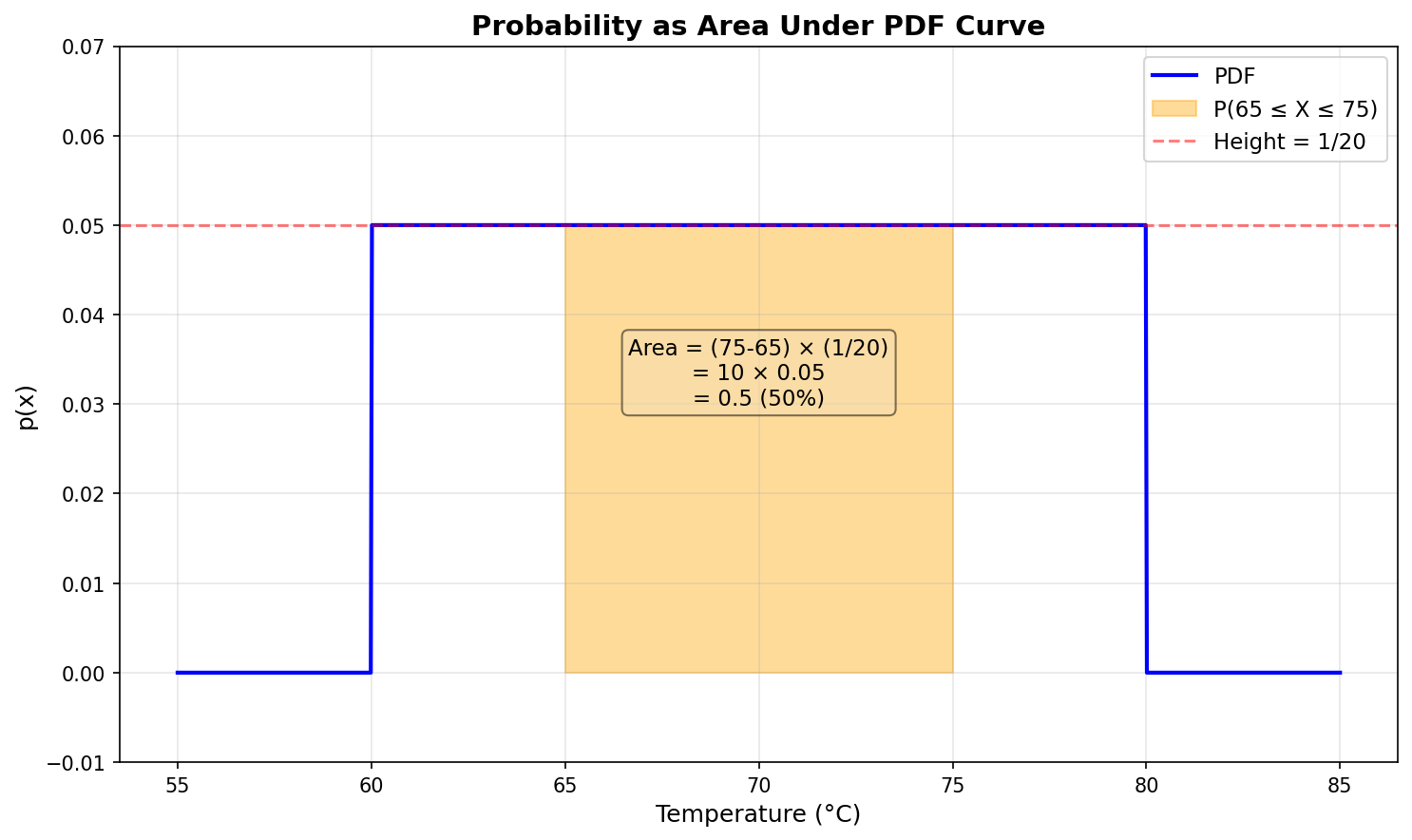

- ✅ “What’s P(500g ≤ weight ≤ 510g)?” (answer: some positive number)

Key insight: In continuous probability, we measure area not count.

Probability Density Functions (PDFs)

A probability density function (PDF) is a function $p(x)$ that tells you the relative likelihood of different values.

Important properties:

- $p(x) \geq 0$ for all $x$ (density is never negative)

- $\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} p(x) , dx = 1$ (total probability is 1)

- $P(a \leq X \leq b) = \int_a^b p(x) , dx$ (probability is area under curve)

Crucially: $p(x)$ itself is not a probability! It’s a density.

- $p(x)$ can be greater than 1

- Only the area under $p(x)$ is a probability

No Calculus? No Problem!

Don’t worry if you haven’t seen integrals (∫) before!

Think of it this way:

- Discrete: Probability = counting + dividing

- Continuous: Probability = measuring area under a curve

$$\int_a^b p(x) , dx \quad \text{means} \quad \text{“area under } p(x) \text{ from } a \text{ to } b\text{”}$$

GenJAX will compute these areas for you. You don’t need to do calculus by hand!

Visualizing PDF vs Probability

Let’s see this with a simple example: a uniform distribution from 0 to 1.

| |

Click to show visualization code

| |

Key observations:

- The PDF is flat at height 1.0 (uniform density)

- $P(0.3 \leq X \leq 0.7) = \text{area} = \text{width} \times \text{height} = 0.4 \times 1.0 = 0.4$

- $P(X = 0.5 \text{ exactly}) = \text{area of vertical line} = 0$

The Uniform Distribution

The simplest continuous distribution is the uniform distribution.

Definition: A random variable $X$ is uniformly distributed on $[a, b]$ if all values in that range are equally likely.

PDF: $$p(x) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{b-a} & \text{if } a \leq x \leq b \ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

Intuition: The PDF is flat (constant) across the allowed range. The height is $\frac{1}{b-a}$ so that the total area equals 1.

In notation: $X \sim \text{Uniform}(a, b)$

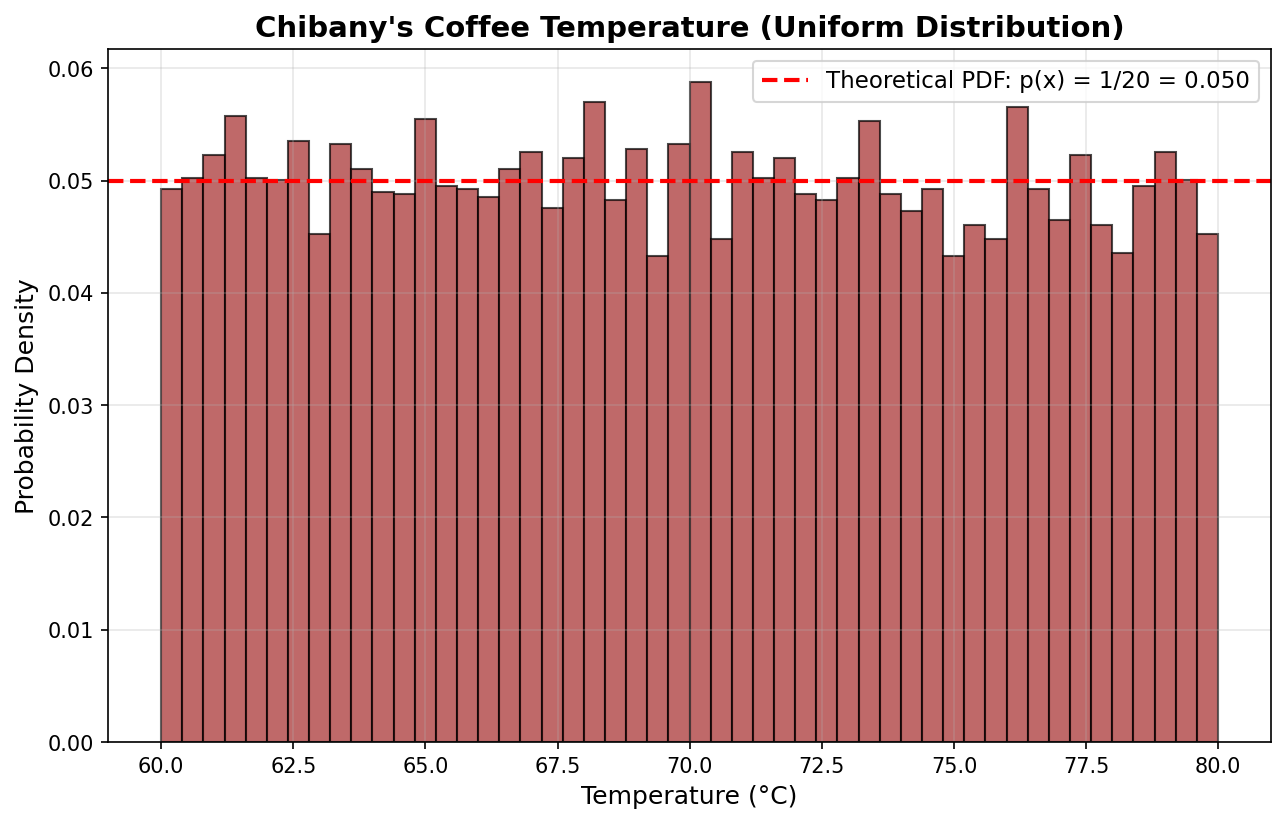

Example: Uniform Coffee Temperature

Chibany’s office coffee machine is unreliable. The temperature of their morning coffee is uniformly distributed between 60°C and 80°C.

| |

Click to show visualization code

| |

| |

Output:

P(temp < 65°C) = 0.250

P(70°C ≤ temp ≤ 75°C) = 0.250

P(temp > 75°C) = 0.250Theoretical calculation:

- $P(\text{temp} < 65) = \frac{65-60}{80-60} = \frac{5}{20} = 0.25$ ✓

- $P(70 \leq \text{temp} \leq 75) = \frac{75-70}{80-60} = \frac{5}{20} = 0.25$ ✓

- $P(\text{temp} > 75) = \frac{80-75}{80-60} = \frac{5}{20} = 0.25$ ✓

Perfect match! GenJAX simulations approximate the theoretical probabilities.

Cumulative Distribution Functions (CDFs)

Another way to work with continuous distributions is through the cumulative distribution function (CDF).

Definition: The CDF of a random variable $X$ is: $$F_X(x) = P(X \leq x) = \int_{-\infty}^x p(t) , dt$$

It tells you: “What’s the probability that X is at most x?”

Properties:

- $F_X(-\infty) = 0$ (probability of being ≤ negative infinity is 0)

- $F_X(\infty) = 1$ (probability of being ≤ infinity is 1)

- $F_X$ is non-decreasing (never goes down)

- $P(a \leq X \leq b) = F_X(b) - F_X(a)$ (subtract CDFs to get probabilities)

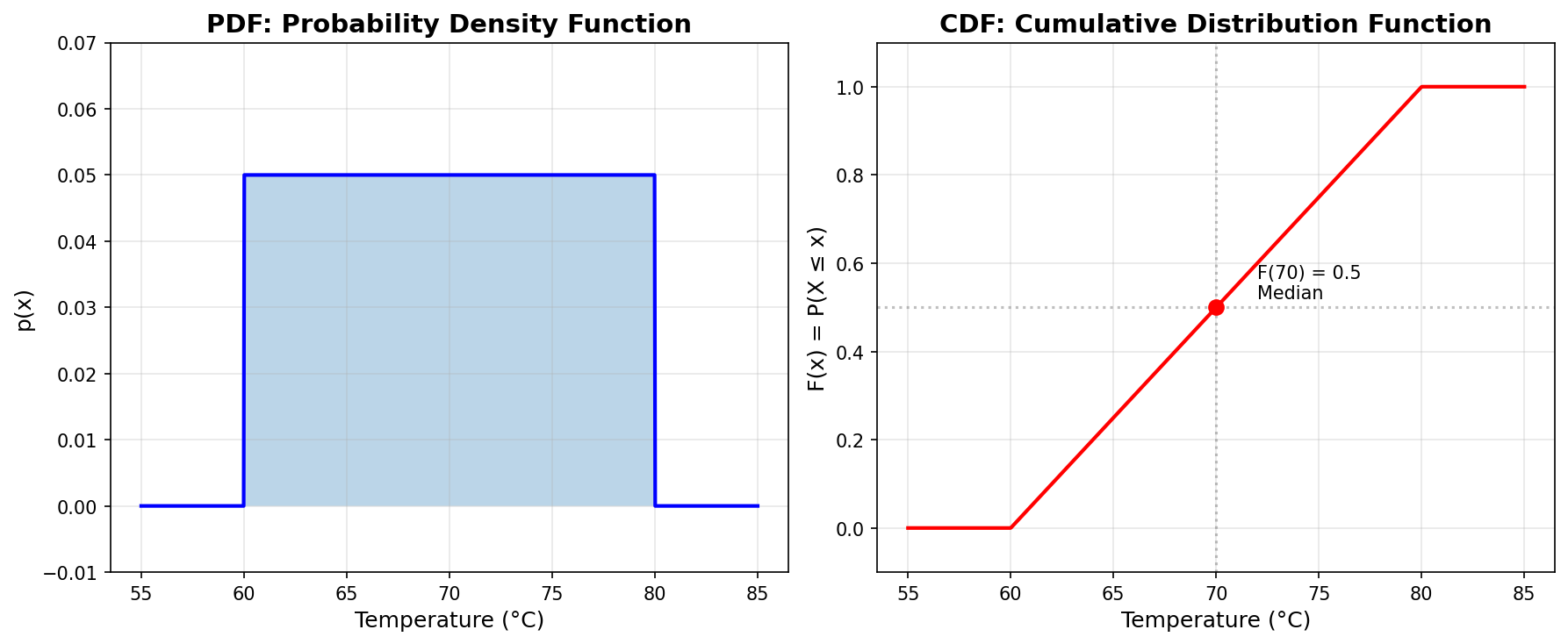

CDF for Uniform Distribution

For $X \sim \text{Uniform}(a, b)$:

$$F_X(x) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } x < a \ \frac{x-a}{b-a} & \text{if } a \leq x \leq b \ 1 & \text{if } x > b \end{cases}$$

Let’s visualize this for Chibany’s coffee:

| |

Click to show visualization code

| |

Reading the CDF:

- At x = 70°C, F(70) = 0.5: “50% of coffees are ≤ 70°C”

- At x = 65°C, F(65) = 0.25: “25% of coffees are ≤ 65°C”

- At x = 75°C, F(75) = 0.75: “75% of coffees are ≤ 75°C”

PDF vs CDF

When to use each?

PDF ($p(x)$):

- Shows relative likelihood of values

- Use for: visualization, understanding shape

- $P(a \leq X \leq b) = \int_a^b p(x) dx$ (area under curve)

CDF ($F_X(x)$):

- Shows cumulative probability up to x

- Use for: calculations, percentiles

- $P(a \leq X \leq b) = F_X(b) - F_X(a)$ (subtract values)

Relationship: $p(x) = \frac{d}{dx} F_X(x)$ (PDF is derivative of CDF)

Both describe the same distribution, just from different perspectives!

Connecting Back to Chibany’s Bentos

Remember Chibany’s observation: bento weights aren’t exactly 500g and 350g - they vary!

Now we have the tools to model this variation:

- Tonkatsu bentos: Weight is continuous around 500g

- Hamburger bentos: Weight is continuous around 350g

But a uniform distribution doesn’t fit. Why?

- Uniform says all values equally likely in a range

- But we see weights cluster near 500g and 350g

- Values far from the center are less likely

We need a distribution that:

- Has a peak (mode) at the center

- Gets less likely as you move away

- Has controlled spread (some bentos vary more than others)

That distribution is the Gaussian (Normal) distribution - the famous bell curve!

That’s what we’ll study in the next chapter.

Summary

Chapter 2 Summary: Key Takeaways

The Challenge:

- Weight is continuous, not discrete

- Infinitely many possible values between any two points

- Every specific value has probability zero!

The Solution: Probability Densities

- PDF $p(x)$: Probability density at each point

- $P(a \leq X \leq b) = \int_a^b p(x) dx$: Probability is area under curve

- $p(x)$ itself is not a probability (can be > 1!)

The Uniform Distribution:

- Simplest continuous distribution

- All values equally likely in a range $[a, b]$

- PDF: $p(x) = \frac{1}{b-a}$ for $a \leq x \leq b$

- CDF: $F_X(x) = \frac{x-a}{b-a}$ for $a \leq x \leq b$

GenJAX Tools:

jnp.uniform(a, b) @ "addr": Sample from uniform distribution- Simulation approximates probabilities: $P(\text{event}) \approx \frac{\text{# times event occurs}}{\text{# simulations}}$

Looking Ahead:

- Need a distribution with a peak and controlled spread

- Enter the Gaussian (Normal) distribution

- The bell curve that models natural variation!

Practice Problems

Problem 1: Waiting Time

Chibany’s bus arrives uniformly between 8:00 AM and 8:20 AM. What’s the probability it arrives:

- a) Before 8:05 AM?

- b) Between 8:10 AM and 8:15 AM?

- c) After 8:18 AM?

Problem 2: GenJAX Simulation

Write a GenJAX generative function for Problem 1 and simulate 10,000 bus arrivals. Verify that your empirical probabilities match the theoretical values.

Problem 3: Why Zero Probability Doesn’t Mean Impossible

If $P(X = 505.0 \text{ exactly}) = 0$, how is it possible that Chibany observed a bento weighing exactly 505.0g?

Next: Chapter 3 - The Gaussian Distribution →

Where we finally meet the bell curve and understand why it’s everywhere in nature!