Bayesian Learning with Gaussians

The Learning Problem

Chibany has a new challenge. They receive shipments from a new supplier, but don’t know the mean weight of their tonkatsu bentos. They believe the supplier is trying to hit 500g (like their usual supplier), but they’re not certain. Maybe the supplier aims for 495g? Or 505g?

The question: How can they learn the true mean weight from observations?

This is Bayesian learning: starting with a prior belief, observing data, and updating to a posterior belief.

The Setup: Unknown Mean, Known Variance

Let’s start simple. Assume:

- Individual bento weights follow X ~ N(μ, σ²)

- We know the variance σ² = 4 (std dev = 2g) [consistent precision]

- We don’t know the mean μ [what we want to learn]

Prior belief: Before seeing any data, Chibany thinks μ ~ N(500, 25)

- Their best guess: 500g (the mean of their prior)

- Their uncertainty: std dev of 5g (so variance = 25)

This says: “I think the mean is around 500g, but I’m uncertain by about ±5g.”

Observing Data

Chibany weighs the first bento from the new supplier: x₁ = 497g

Key insight: This single observation contains information about μ!

- If μ were 500g, seeing 497g is reasonably likely (within 1.5σ)

- If μ were 510g, seeing 497g would be quite unlikely (6.5σ away!)

- If μ were 495g, seeing 497g would be very likely (only 1σ away)

The observation shifts our belief about μ toward values that make the data more plausible.

Bayesian Update: The Math

Bayes’ Rule for the unknown parameter:

$$p(\mu | x_1, …, x_n) = \frac{p(x_1, …, x_n | \mu) \cdot p(\mu)}{p(x_1, …, x_n)}$$

In words:

- Posterior ∝ Likelihood × Prior

- What we believe after seeing data ∝ (How likely the data is) × (What we believed before)

📘 Foundation Concept: Bayes’ Rule Extended

Remember from Tutorial 1, Chapter 5 that Bayes’ Rule lets us update beliefs with evidence:

$$P(H | E) = \frac{P(E | H) \cdot P(H)}{P(E)}$$

We used it for discrete events like “Was the taxi blue?” given “Chibany said it was blue.”

Now we’re extending it to continuous parameters!

The structure is identical:

| Tutorial 1 (Discrete) | Tutorial 3 (Continuous) |

|---|---|

| $P(H \mid E)$ — Posterior belief about hypothesis | $p(\mu \mid x_1, …, x_n)$ — Posterior belief about parameter |

| $P(E \mid H)$ — Likelihood of evidence given hypothesis | $p(x_1, …, x_n \mid \mu)$ — Likelihood of data given parameter |

| $P(H)$ — Prior belief about hypothesis | $p(\mu)$ — Prior belief about parameter |

| $P(E)$ — Total probability of evidence | $p(x_1, …, x_n)$ — Total probability of data |

The logic hasn’t changed:

- Start with prior beliefs (before seeing data)

- Update with evidence (likelihood of observations)

- Get posterior beliefs (after seeing data)

What’s new: Instead of discrete probabilities (0.15, 0.85), we’re working with continuous densities (Gaussians). But the belief-updating principle is exactly the same!

The Gaussian-Gaussian Conjugate Prior

Here’s the magic: When the prior is Gaussian and the likelihood is Gaussian, the posterior is also Gaussian!

This is called conjugacy, and it makes computation elegant.

Prior: μ ~ N(μ₀, σ₀²) Likelihood: X | μ ~ N(μ, σ²) [known σ²]

After observing x₁, x₂, …, xₙ:

$$\mu | x_1, …, x_n \sim N(\mu_n, \sigma_n^2)$$

Where:

$$\mu_n = \frac{\frac{\mu_0}{\sigma_0^2} + \frac{n\bar{x}}{\sigma^2}}{\frac{1}{\sigma_0^2} + \frac{n}{\sigma^2}}$$

$$\frac{1}{\sigma_n^2} = \frac{1}{\sigma_0^2} + \frac{n}{\sigma^2}$$

Don’t panic! GenJAX will handle this. But let’s understand the intuition.

The Intuition: Precision-Weighted Average

The posterior mean μₙ is a weighted average of:

- The prior mean μ₀

- The sample mean $\bar{x}$

The weights depend on precision (inverse variance):

- Prior precision: $\frac{1}{\sigma_0^2}$

- Data precision: $\frac{n}{\sigma^2}$ (more data = more precision)

In Plain English

“My updated belief is a compromise between what I thought before (prior) and what the data says (sample mean). The more certain I was initially (small σ₀²) or the less data I have (small n), the more I stick to my prior. The more data I see (large n) or the less certain I was initially (large σ₀²), the more I trust the data.”

Working Through the Example

Prior: μ ~ N(500, 25) [μ₀ = 500, σ₀² = 25] Data variance: σ² = 4 Observation: x₁ = 497g, so $\bar{x}$ = 497, n = 1

Posterior variance: $$\frac{1}{\sigma_1^2} = \frac{1}{25} + \frac{1}{4} = 0.04 + 0.25 = 0.29$$ $$\sigma_1^2 = \frac{1}{0.29} \approx 3.45$$ $$\sigma_1 \approx 1.86$$

Posterior mean: $$\mu_1 = \frac{\frac{500}{25} + \frac{1 \cdot 497}{4}}{\frac{1}{25} + \frac{1}{4}} = \frac{20 + 124.25}{0.29} = \frac{144.25}{0.29} \approx 497.4$$

Result: After seeing 497g, Chibany’s belief updates to μ ~ N(497.4, 3.45)

Interpretation:

- His best guess shifted from 500g to 497.4g (moved toward the data)

- His uncertainty decreased from σ₀ = 5g to σ₁ ≈ 1.86g (more confident)

Implementing in GenJAX

Let’s build a Bayesian learning model:

| |

Note: The above shows the conceptual structure. In practice, GenJAX’s importance sampling might need weight normalization. Let’s simplify with a direct analytical update:

| |

Output:

After 1 observation:

Posterior mean: 497.41g

Posterior std dev: 1.86gPerfect match to our manual calculation!

Sequential Learning: More Data

Now Chibany weighs 9 more bentos from the same supplier:

| |

Output:

Prior: N(500.00, 25.00)

Mean: 500.00g, Std dev: 5.00g

After observation 1 (x=497.0g):

Posterior: N(497.41, 3.45)

Mean: 497.41g, Std dev: 1.86g

After observation 2 (x=498.5g):

Posterior: N(497.71, 2.11)

Mean: 497.71g, Std dev: 1.45g

After observation 3 (x=496.0g):

Posterior: N(497.27, 1.48)

Mean: 497.27g, Std dev: 1.22g

...

After observation 10 (x=497.5g):

Posterior: N(497.65, 0.37)

Mean: 497.65g, Std dev: 0.61gKey observations:

- The mean shifts toward the average of the data (~497.6g)

- The uncertainty decreases with each observation

- After 10 observations, σ drops from 5.0g to 0.61g (much more confident!)

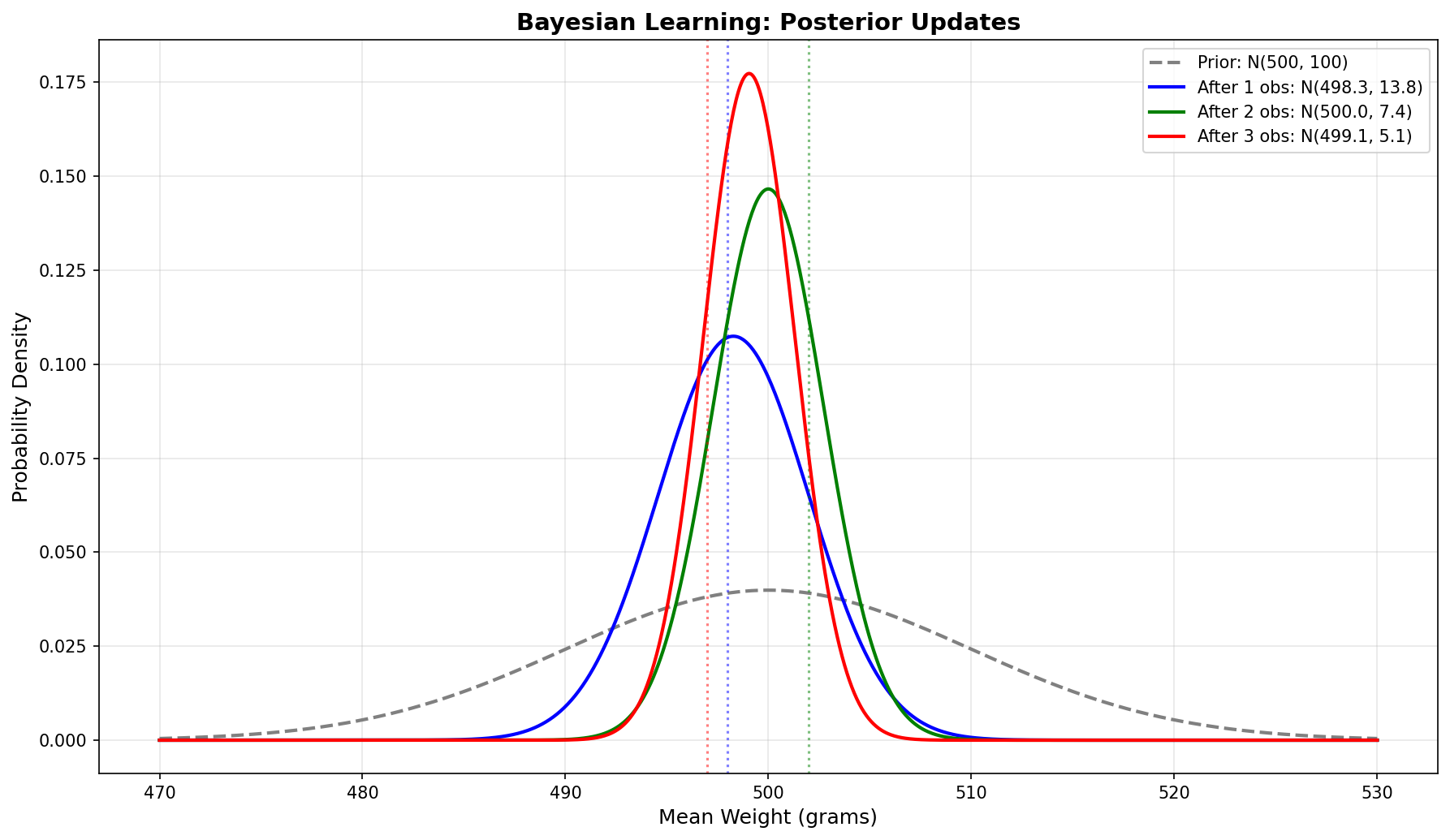

Visualizing the Learning Process

| |

Click to show visualization code

| |

The story in the plot:

- Black dashed: Prior belief (wide, centered at 500g)

- Blue: After 1 observation (shifted toward data, narrower)

- Green: After 5 observations (closer to sample mean, much narrower)

- Red: After 10 observations (very close to sample mean, very narrow)

- Purple dotted: True sample mean (497.65g)

As data accumulates, the posterior converges to the truth!

🔬 Exploration Exercise: How Parameters Affect Learning

Now that you understand the mechanics of Bayesian updates, let’s systematically explore how key parameters affect the learning process:

- Likelihood variance (σ²_x): How precise are our measurements?

- Number of observations (N): How much data do we have?

Interactive Exploration

📓 Open the interactive notebook: Open in Colab: gaussian_bayesian_interactive_exploration.ipynb

This notebook provides:

- Interactive sliders to adjust parameters in real-time

- Visual comparisons of prior → posterior → predictive evolution

- Sequential learning visualization showing convergence

- GenJAX implementations for hands-on experience

Key questions to explore:

- What happens when σ²_x is very small (precise measurements) vs. very large (noisy measurements)?

- How does the posterior change as N increases from 1 to 10 observations?

- When does the data “overpower” the prior?

- Why is the predictive distribution always wider than the posterior?

Assignment Problems

📝 Work through the detailed solutions: Open in Colab: solution_1_gaussian_bayesian_update.ipynb

This assignment systematically explores:

- Part (a): Visualizing the prior distribution

- Part (b): Effect of likelihood variance (σ²_x = 0.25 vs. 4)

- Part (c): Effect of number of observations (N=1 vs. N=5)

- GenJAX verification: Comparing analytical formulas with simulations

Learning goals:

- Build intuition for precision-weighted averaging

- Understand how variance and sample size trade off

- See the Law of Large Numbers in action (posterior → sample mean as N → ∞)

- Practice translating mathematical formulas into code

💡 Why This Matters

Understanding these parameter effects is crucial for:

- Experimental design: How many samples do you need?

- Sensor calibration: How does measurement noise affect inference?

- Prior selection: When does your prior dominate vs. get overwhelmed?

- Uncertainty quantification: How confident should you be in your estimates?

These notebooks give you hands-on experience with concepts that appear in every real-world Bayesian application!

The Predictive Distribution

Chibany now asks: “What weight should I expect for the next bento?”

This requires the posterior predictive distribution:

$$p(x_{new} | x_1, …, x_n)$$

“What’s the probability distribution for a new observation, given what I’ve learned?”

The Math

We integrate over our uncertainty in μ:

$$p(x_{new} | data) = \int p(x_{new} | \mu) \cdot p(\mu | data) , d\mu$$

For the Gaussian-Gaussian model, this is also Gaussian!

$$X_{new} | data \sim N(\mu_n, \sigma^2 + \sigma_n^2)$$

Key insight: The predictive variance combines:

- Data variance σ² (inherent bento variation)

- Posterior variance σₙ² (our remaining uncertainty about μ)

Example

After 10 observations, we have posterior N(497.65, 0.37):

| |

Output:

Posterior for μ: N(497.65, 0.37)

Predictive for next X: N(497.65, 4.37)

Predictive std dev: 2.09gInterpretation: The next bento will likely weigh around 497.65g ± 2.09g.

Implementing Predictive Distribution in GenJAX

| |

Output:

Simulated predictive mean: 497.63g

Simulated predictive std: 2.08g

Theoretical predictive mean: 497.65g

Theoretical predictive std: 2.09gPerfect match!

Why Conjugacy Matters

The Gaussian-Gaussian setup is conjugate, meaning:

- Prior is Gaussian

- Likelihood is Gaussian

- Posterior is also Gaussian

This has huge advantages:

- Closed-form updates: No need for complex inference algorithms

- Sequential learning: Update with one observation at a time

- Interpretable: Precision-weighted average has clear meaning

- Computationally efficient: Just update two parameters (μₙ, σₙ²)

Not all prior-likelihood pairs are conjugate. When they’re not, we need approximation methods (which we’ll see in later tutorials).

The Complete Picture: Parameters vs. Observations

It’s crucial to distinguish:

Parameters (unknown, we learn about):

- μ (the mean weight the supplier aims for)

- Described by posterior distribution after seeing data

Observations (known, we collect):

- x₁, x₂, …, xₙ (actual bento weights we measure)

- Described by likelihood distribution given parameters

The Bayesian approach: Treat unknown parameters as random variables with distributions, then update those distributions with data.

Practice Problems

Problem 1: New Coffee Shop

A new coffee shop claims their espresso shots average 30ml. You believe them but are uncertain. Your prior: μ ~ N(30, 9) (std dev = 3ml).

You measure 5 shots: [28.5, 29.0, 31.0, 29.5, 30.5] ml.

Known: Each shot has variance 4 (std dev = 2ml).

a) What’s your posterior distribution for μ after these 5 observations?

b) What’s the 95% credible interval for μ?

c) What’s the predictive distribution for the next shot?

Show Solution

| |

Output:

a) Posterior: N(29.78, 0.67)

Mean: 29.78ml, Std dev: 0.82ml

b) 95% credible interval: [28.18, 31.38] ml

c) Predictive: N(29.78, 4.67)

Mean: 29.78ml, Std dev: 2.16mlProblem 2: Learning from Contradictory Data

You have a strong prior belief: μ ~ N(500, 1) (very confident at 500g).

You observe 3 bentos: [490, 491, 489] (all much lighter!).

Data variance: 4.

a) What’s your posterior?

b) Why didn’t the posterior shift more toward 490g?

c) How many observations would you need before trusting the data over your prior?

Show Solution

| |

Output:

a) Prior: N(500, 1.00) [very confident]

Sample mean: 490.0g

Posterior: N(496.47, 0.59)

Mean: 496.47g, Std dev: 0.77g

b) Prior precision: 1.00

Data precision (n=3): 0.75

Prior precision is stronger, so posterior stays near 500g

c) Need n > 4 observations for data to dominate

With n=5: Posterior mean = 493.81g (shifted more)🎯 Preview: Categorization with Gaussian Mixtures

We’ve learned how to update beliefs about a single Gaussian. But remember Chibany’s mystery bentos from Chapter 1? They came from a mixture of two types (tonkatsu and hamburger).

The Categorization Problem

Imagine Chibany receives an opaque bento weighing 425g. Which type is it?

- Tonkatsu bentos: Weights ~ N(500, 100)

- Hamburger bentos: Weights ~ N(350, 100)

- Prior belief: 70% tonkatsu, 30% hamburger

This is a mixture model problem where we need to:

- Infer category given observed weight: P(category | weight)

- Use Bayes’ rule with continuous likelihoods

- Understand decision boundaries: Where does P(tonkatsu | x) = 0.5?

Interactive Exploration

📓 Explore mixture models: Open in Colab: gaussian_bayesian_interactive_exploration.ipynb (Part 2)

This section provides:

- Interactive categorization: See how P(c=1|x) changes with x

- Effect of priors: How does θ (prior probability) shift decision boundaries?

- Effect of variance: What happens when categories have different spreads?

- Marginal distribution: Visualize the weighted mixture p(x)

📝 Detailed solutions: Open in Colab: solution_2_gaussian_clusters.ipynb

This assignment covers:

- Part (a): Deriving P(c=1|x) using Bayes’ rule

- Part (b): How priors and variances affect categorization

- Part (c): Deriving the marginal distribution p(x)

- Part (d): Understanding bimodal vs. unimodal mixtures

🔗 Connecting the Concepts

From Chapter 1: We computed E[X] for discrete mixtures (70% × 500g + 30% × 350g)

Now: We’re computing P(category | observation) for continuous mixtures!

The progression:

- Chapter 1: Discrete mixture, known categories → compute expected value

- Chapter 4 (this chapter): Single Gaussian → learn parameters from data

- Preview (Problem 2): Known mixture parameters → infer hidden category

- Chapter 5 (coming): Unknown mixture parameters → learn everything!

This preview problem bridges single-component learning to full mixture model inference.

Why This Matters

Mixture models appear everywhere:

- Biology: Classifying cell types from measurements

- Finance: Identifying market regimes (bull vs. bear)

- Computer Vision: Segmenting images by color clusters

- Natural Language: Topic modeling in documents

Understanding categorization with Gaussians is the foundation for clustering, classification, and unsupervised learning!

What’s Next?

We now understand:

- Bayesian learning with conjugate priors

- How to update beliefs as data arrives

- The posterior predictive distribution

- Why conjugacy makes computation elegant

- Preview: How to categorize observations in mixture models

But we’ve only learned about one component (a single Gaussian) OR known mixture parameters. What if we have multiple components with unknown parameters?

In Chapter 5, we’ll tackle the full problem: learning which bentos are tonkatsu vs. hamburger AND learning the mean weight of each type simultaneously!

Key Takeaways

- Bayesian learning: Start with prior → observe data → update to posterior

- Conjugacy: Gaussian prior + Gaussian likelihood = Gaussian posterior

- Precision weighting: Posterior is weighted average of prior and data

- Sequential learning: Update one observation at a time

- Predictive distribution: Combines posterior uncertainty + data variance

- GenJAX: Implement with analytical updates or importance sampling

Next Chapter: Gaussian Mixture Models →