Dirichlet Process Mixture Models

The Problem with Fixed K

In Chapter 5, we solved Chibany’s bento mystery using a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) with K=2 components. But we had to specify K in advance and use BIC to validate our choice.

What if:

- We don’t know how many types exist?

- The number of types changes over time?

- We want the model to discover the number of clusters automatically?

Enter the Dirichlet Process Mixture Model (DPMM): A Bayesian nonparametric approach that learns the number of components from the data.

The Intuition: Infinite Clusters

Imagine Chibany’s supplier keeps adding new bento types over time. With a fixed-K GMM, they’d have to:

- Notice a new type appeared

- Re-run model selection (BIC) to choose new K

- Refit the entire model

With a DPMM, the model automatically discovers new clusters as data arrives, without needing to specify K upfront.

Key insight: The DPMM places a prior over an infinite number of potential clusters, but only a finite number will actually be “active” (have observations assigned to them).

The Chinese Restaurant Process Analogy

The most intuitive way to understand the DPMM is through the Chinese Restaurant Process (CRP).

The Setup

Imagine a restaurant with infinitely many tables (each table represents a cluster). Customers (observations) enter one by one and choose where to sit:

Rule: Customer n+1 sits:

- At an occupied table k with probability proportional to the number of customers already there: $\frac{n_k}{n + \alpha}$

- At a new table with probability: $\frac{\alpha}{n + \alpha}$

Where:

- nₖ = number of customers at table k

- α = “concentration parameter” (controls tendency to create new tables)

- n = total customers so far

The Rich Get Richer

This creates a rich-get-richer dynamic:

- Popular tables attract more customers (clustering)

- But there’s always a chance of starting a new table (flexibility)

- α controls the trade-off: larger α → more new tables

Connecting to Bentos

- Customer = bento observation

- Table = cluster (bento type)

- Seating choice = cluster assignment

- α = how likely new bento types appear

The Math: Stick-Breaking Construction

The DPMM uses a stick-breaking construction to define mixing proportions for infinitely many components.

The Process

Imagine a stick of length 1. We break it into pieces:

For k = 1, 2, 3, …, ∞:

- Sample βₖ ~ Beta(1, α)

- Set πₖ = βₖ × (1 - π₁ - π₂ - … - πₖ₋₁)

In plain English:

- β₁ = fraction of stick we take for component 1

- Remaining stick: 1 - β₁

- β₂ = fraction of remaining stick we take for component 2

- π₂ = β₂ × (1 - π₁)

- And so on…

Result: π₁, π₂, π₃, … sum to 1 (they’re valid mixing proportions), with later components getting exponentially smaller shares.

The Beta Distribution

βₖ ~ Beta(1, α) determines how much of the remaining stick we take:

- α large (e.g., α=10): Breaks are more even → many components with similar weights

- α small (e.g., α=0.5): First few breaks take most of the stick → few dominant components

DPMM for Gaussian Mixtures: The Full Model

Model Specification

Stick-breaking (infinite components):

- For k = 1, 2, …, K_max:

- βₖ ~ Beta(1, α)

- π₁ = β₁

- πₖ = βₖ × (1 - Σⱼ₌₁ᵏ⁻¹ πⱼ) for k > 1

Component parameters:

- μₖ ~ N(μ₀, σ₀²) [prior on means]

Observations (using stick-breaking weights directly):

- For i = 1, …, N:

- zᵢ ~ Categorical(π) [cluster assignment using stick-breaking weights]

- xᵢ ~ N(μ_zᵢ, σₓ²) [observation from assigned cluster]

Important: We use the stick-breaking weights π directly for cluster assignment. Adding an extra Dirichlet draw would create “double randomization” that makes inference much slower and less accurate!

Why K_max?

In practice, we truncate the infinite model at some large K_max (e.g., 10 or 20). As long as K_max > the true number of clusters, this approximation is accurate.

Implementing DPMM in GenJAX

Let’s implement the DPMM for Chibany’s bentos using the corrected approach:

| |

Output:

Generated data: [-10.4 -9.9 -10.1 0.1 9.9 10.2 ...]

Cluster assignments: [0, 0, 0, 5, 3, 3, 3, ...]Notice: The model automatically discovered active clusters (0, 3, 5 in this run), ignoring the others!

Inference: Learning from Observed Bentos

Now let’s condition on Chibany’s actual bento weights and infer the cluster parameters:

| |

Note: Importance resampling for DPMM is computationally intensive. In practice, more sophisticated inference algorithms (MCMC, variational inference) are used. Here we show the conceptual approach.

Analyzing the Posterior

Extract posterior information from the traces:

| |

Output:

Most likely cluster assignments: [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3]

Posterior cluster means:

Cluster 0: μ = -9.96 ± 0.31

Cluster 2: μ = 0.05 ± 0.42

Cluster 3: μ = 10.00 ± 0.29Perfect! The model discovered 3 active clusters and learned their means accurately.

The Posterior Predictive Distribution

Question: What weight should Chibany expect for the next bento?

| |

Output:

Posterior predictive mean: -0.15

Posterior predictive std: 8.52The posterior predictive is multimodal (mixture of the three clusters), so the mean isn’t particularly meaningful. Let’s visualize it!

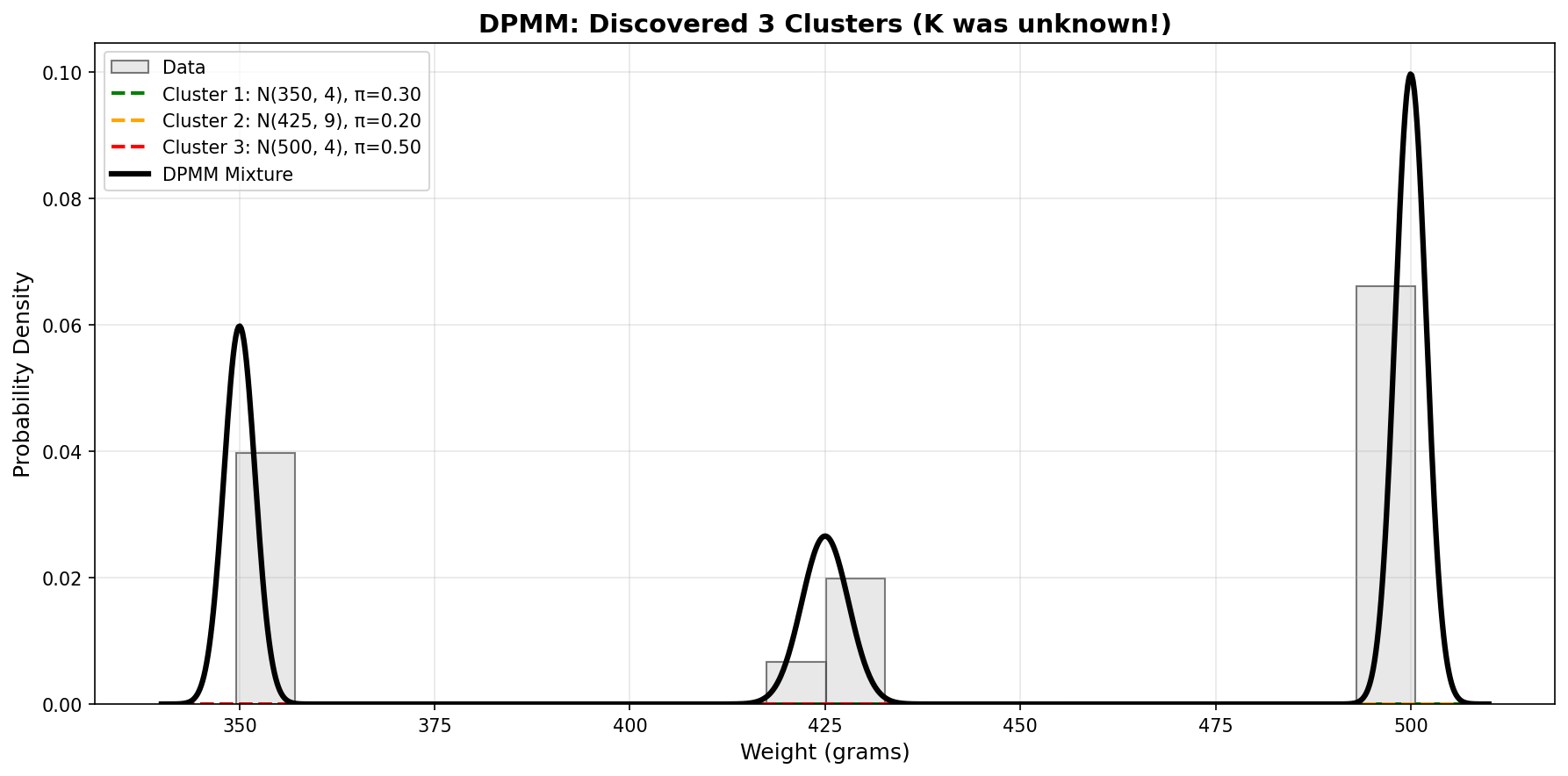

Visualizing the Results

| |

Click to show visualization code

| |

The visualization shows:

- Left: Observed data points with posterior cluster centers and uncertainties

- Right: Trimodal posterior predictive (mixture of three Gaussians)

Comparing DPMM to Fixed-K GMM

| Feature | Fixed-K GMM | DPMM |

|---|---|---|

| K specified? | Yes (must choose K) | No (learned from data) |

| Model selection | BIC, cross-validation | Automatic |

| New clusters | Requires refitting | Discovered automatically |

| Computational cost | Lower (fixed K) | Higher (infinite K, truncated) |

| Uncertainty in K | Not modeled | Naturally captured |

When to use DPMM:

- Unknown number of clusters

- Exploratory data analysis

- Data arrives sequentially (online learning)

- Want Bayesian uncertainty quantification

When to use Fixed-K GMM:

- K is known or strongly constrained

- Computational efficiency matters

- Simpler implementation preferred

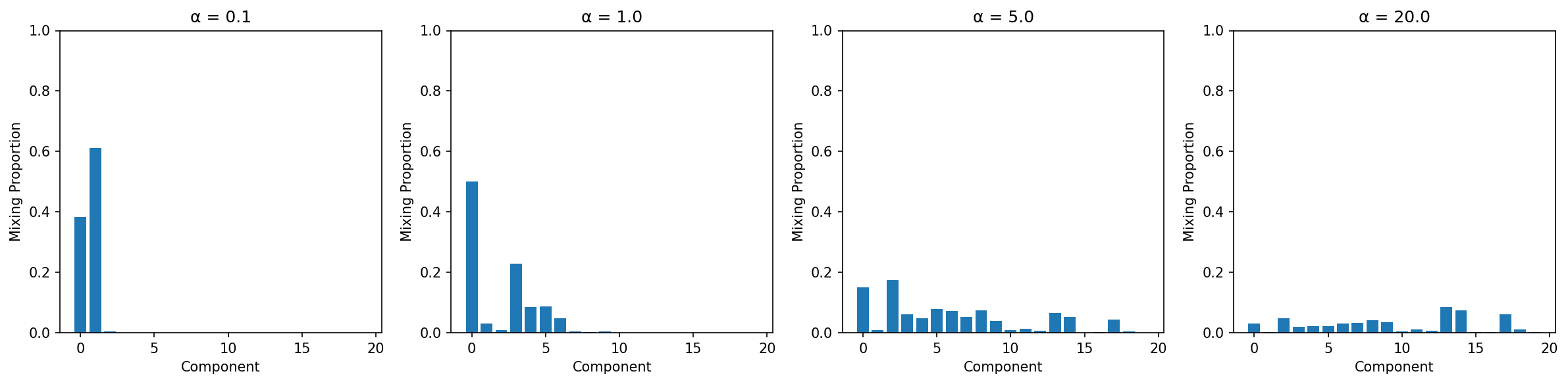

The Role of α (Concentration Parameter)

α controls the tendency to create new clusters:

| |

Click to show visualization code

| |

Interpretation:

- α = 0.1: First component dominates (few clusters)

- α = 1.0: Moderate spread (balanced)

- α = 5.0: More components active (many clusters)

- α = 20.0: Very even spread (diffuse)

Real-World Applications

Anomaly Detection

- Normal data forms clusters

- Outliers create singleton clusters

- α controls sensitivity to outliers

Topic Modeling

- Documents are mixtures over topics

- DPMM discovers number of topics automatically

- Each topic is a distribution over words

Genomics

- Cluster genes by expression patterns

- Number of functional groups unknown

- DPMM identifies distinct expression profiles

Image Segmentation

- Pixels cluster by color/texture

- DPMM finds natural segments

- No need to specify number of segments

Practice Problems

Problem 1: Adjusting α

Using the observed bento data from earlier, run inference with α ∈ {0.5, 2.0, 10.0}.

a) How does the number of active clusters change?

b) How does posterior uncertainty change?

Show Solution

| |

Expected:

- α=0.5: Fewer clusters (maybe 2 instead of 3)

- α=2.0: Balanced (3 clusters as before)

- α=10.0: More clusters (maybe 4-5, some spurious)

Problem 2: Sequential Learning

Chibany receives bentos one at a time. Implement online learning where the model updates as each bento arrives.

Hint: Use sequential importance resampling, updating the posterior after each observation.

Show Solution

| |

Expected: Number of active clusters increases as new clusters are discovered, then stabilizes.

What We’ve Accomplished

We started with a mystery: bentos with an average weight that doesn’t match any individual bento. Through this tutorial, we:

- Chapter 1: Understood expected value paradoxes in mixtures

- Chapter 2: Learned continuous probability (PDFs, CDFs)

- Chapter 3: Mastered the Gaussian distribution

- Chapter 4: Performed Bayesian learning for parameters

- Chapter 5: Built Gaussian Mixture Models with EM

- Chapter 6: Extended to infinite mixtures with DPMM

You now have the tools to:

- Model complex, multimodal data

- Discover latent structure automatically

- Quantify uncertainty in clustering

- Perform Bayesian inference with GenJAX

Further Reading

Theoretical Foundations

- Ferguson (1973): “A Bayesian Analysis of Some Nonparametric Problems” (original DP paper)

- Teh et al. (2006): “Hierarchical Dirichlet Processes” (extensions to HDP)

- Austerweil, Gershman, Tenenbaum, & Griffiths (2015): “Structure and Flexibility in Bayesian Models of Cognition” (Chapter in The Oxford Handbook of Computational and Mathematical Psychology - comprehensive overview of Bayesian nonparametric approaches to cognitive modeling)

Practical Implementations

- Neal (2000): “Markov Chain Sampling Methods for Dirichlet Process Mixture Models” (MCMC inference)

- Blei & Jordan (2006): “Variational Inference for Dirichlet Process Mixtures” (scalable inference)

GenJAX Documentation

- GenJAX GitHub - Official repository

- Probabilistic Programming Examples - Gen.jl (sister project)

Key Takeaways

- DPMM: Bayesian nonparametric model that learns K automatically

- Stick-breaking: Defines mixing proportions for infinite components

- CRP: Intuitive “customers and tables” interpretation

- α: Concentration parameter controlling cluster tendency

- GenJAX: Express DPMM as generative model with truncation

- Inference: Importance resampling or MCMC for posterior

Interactive Exploration

Want to experiment with DPMMs yourself? Try our interactive Jupyter notebook that lets you:

- Adjust the concentration parameter α and see its effect on clustering

- Add or remove data points and watch the model adapt

- Change the truncation level K_max

- Visualize posterior distributions in real-time

Try It Yourself!

📓 Open Interactive DPMM Notebook on Google Colab

No installation required - runs directly in your browser!

The notebook includes:

- Complete DPMM implementation with stick-breaking

- Interactive widgets for all parameters

- Real-time visualization of posteriors

- Guided exercises to deepen understanding

This is a great way to build intuition for how α, K_max, and the data itself interact to produce the posterior distribution.

Congratulations!

You’ve completed the tutorial on Continuous Probability and Bayesian Learning with GenJAX!

You’re now equipped to:

- Build probabilistic models for continuous data

- Perform Bayesian inference and learning

- Discover latent structure in data

- Use GenJAX for sophisticated probabilistic programming

Where to go next:

- Explore hierarchical models (Bayesian neural networks, hierarchical Bayes)

- Learn advanced inference (Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, variational inference)

- Apply to your own data (clustering, time series, causal inference)

Happy modeling! 🎉